One day, during the tumultuous years of the Civil War, a number of Union troops gathered on the front lawn of the White House, awaiting their Commander in Chief’s review. Abraham Lincoln stepped out onto the portico with an American flag firmly gripped in his large hands. The men’s excitement at seeing their president in the flesh quickly turned to bewilderment when an extremely large Confederate flag – the symbol of all that these men were prepared to oppose at the cost of their own lives – appeared behind President Lincoln. The halting, uncertain way that the flag moved indicated that the bearer was possibly a tad bit too small to be wielding such a large item. Perhaps the perplexed look on the men’s faces alerted Lincoln to the disturbance, or maybe he felt a slight breeze from the flag’s movements. Whatever the case, Lincoln spun around and found – much to his embarrassment – his little son, Tad, waving this large Confederate flag with gusto. The president “”pinioned his bad boy and the flag in his strong arms and handed them together to an orderly, who carried the offenders within.””1 One wonders what conversations occurred in the Lincoln family that evening around their dinner table!

You might be curious right about now how Tad Lincoln got his hands on a Confederate flag. After all, his father was utterly and completely determined to preserve the Union, even though that objective required a tremendous cost in both blood and treasure for the nation, and even for Lincoln himself. In fact, the loss of one of Lincoln’s dear friends is how this flag came to be in his family’s possession. So, who was this friend, and what was his relationship to Lincoln? And, how did this friend’s death result in the Lincoln family owning a Confederate flag?

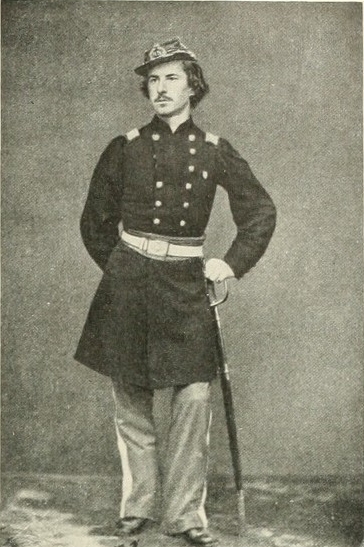

Col. Elmer Ellsworth

One of Lincoln’s dearest friends at the start of the Civil War was a young man by the name of Elmer Ellsworth. If his is a new name to you, you are in good company! I honestly knew nothing of Ellsworth until I started writing this post. However, Ellsworth was actually quite famous during the Civil War, and achieved this notoriety in a few ways. For one thing, Ellsworth’s friendship with Lincoln made him known to the public, as did his involvement in military drills and units before the Civil War started. Thirdly, and far more tragically, Ellsworth found his fame through the misfortune of being the first officer killed in the Civil War.2

Before meeting his quick and tragic end, Ellsworth’s life was marked by difficulty, perseverance, and true determination to follow his passions in life. While Ellsworth was born to a middle class family, he demonstrated a keen interest in all things military from an early age. However, his hopes of attending West Point were squashed by a lack of money and education.3 Ellsworth then decided to seek his fortune in Chicago, but an unsuccessful business venture left him impoverished for a number of years before he took up the law. Still, Ellsworth pursued his martial dreams by continuing to study the military even while he worked as a law clerk.4 Through these studies and through reading newspaper reports, Ellsworth learned of the Zouaves, French soldiers who fought in the Crimean War while wearing garish uniforms and practicing acrobatic drills. To Ellsworth’s delight, he then met a real-life Zouave – a surgeon who had served with one of those unique regiments. Ellsworth’s interest in the Zouaves was put to practical use when, in the late 1850s, he organized a militia company, followed by taking command of the Chicago National Guard Cadets.5

Through the success of Ellsworth’s Zouaves, Lincoln came to know of the young man and the two became fast friends.6 In fact, Lincoln himself worked to bring Ellsworth to his Springfield, Illinois, law office, as Ellsworth wrote to his fiancée: “”Mr. Cook told me that Mr L – especially desired him to leave no means unturned to induce me to come to Springfield.””7 Ellsworth soon became involved in Lincoln’s political career, all from making campaign speeches for him to accompanying him on his journey to Washington, D.C.8 As if this wasn’t enough, Ellsworth played with the little Lincoln children often and lived at the White House himself, demonstrating just how much Lincoln had readily accepted this young man into his family.9 Lincoln’s fondness and respect for Ellsworth were verbally demonstrated when he once called him ““the greatest little man I ever met.””10 This description was an accurate one, as Ellsworth stood at only 5 feet and 6 inches, though his greatness of heart and mind was demonstrated by his service to his country.11

Ellsworth soon had a chance to demonstrate this greatness when the Civil War began in April, 1861. The “little man” traveled back to his original home state of New York, where he organized a regiment of Zouaves – the 11th New York Regiment.12 By May, Ellsworth and his Zouaves were in the D.C. area, which meant that when Virginia seceded from the Union late in the month, the 11th NY was perfectly positioned to cross the Potomac and secure Alexandria from the rebels.13 On May 24th, Ellsworth and his men moved into the town and claimed it for the Union with very little resistance – save for the one incident that would take Ellsworth’s life.14

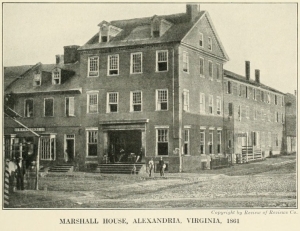

Prior to Ellsworth’s arrival in the town, the secessionist owner of a hotel, the Marshall House, had placed a large Confederate flag on the rooftop in defiance of the Union. This flag was so large that Lincoln could even see it flying from the White House!15 Ellsworth, of course, was not about to let this flag fly a moment longer now that the town was in Union hands. Gathering a couple other men to him, Ellsworth hurried to the hotel with determination to take down the symbol of rebellion. Though Ellsworth successfully removed the flag, the proprietor, roused from his sleep, confronted the young colonel as he attempted to exit the hotel. Despite the efforts of Ellsworth’s companions to protect their leader, the secessionist aimed his shotgun at Ellsworth and delivered a fatal wound to his chest. The “little man” fell to the floor with a thud, never to command his Zouaves again.16 One of Ellsworth’s companions rushed to his side and found a pin Ellsworth had earlier affixed to his uniform now embedded in his chest. This pin bore the apt, if somewhat melodramatic, phrase: “Non Sol Nobis, Sed Pro Patrio (Not for Ourselves, but for Our Country).”17 At only 24 years of age, Ellsworth was the first Union officer to pay the ultimate sacrifice for our country in the Civil War.18

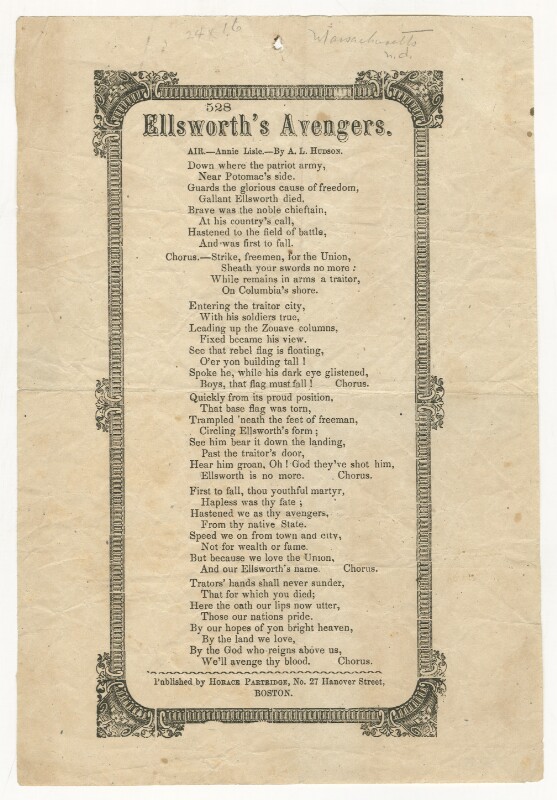

Lincoln’s grief over Ellsworth’s death was acute, and the north soon viewed Ellsworth as a martyr for the Union cause, which eventually led to the creation of a regiment dedicated to his memory.19 When Lincoln heard of Ellsworth’s death, he could not contain his sorrow, according to a senator and a newspaper reporter who happened to meet with Lincoln right after he received the news. As related by these men, Lincoln “‘burst into tears;”” after taking a moment to regain his composure, Lincoln explained: “”I will make no apology, gentlemen for my weakness; but I knew poor Ellsworth well, and held him in great regard.””20 Ellsworth’s funeral was distinguished by the president’s attendance, and by its location in the White House.21 The northern states were rapidly absorbed in commemorative efforts, such as the creation of songs and poems written in Ellsworth’s memory, rising enlistments in the army, and even the formation of a regiment dedicated to the purpose of avenging Ellsworth: the 44th New York Infantry Regiment, popularly known as “Ellsworth’s Avengers.”22

The 44th New York would serve in the Civil War from 1861 through 1864. Comprising New Yorkers, preferably unmarried and tall (no shorter than 5’ 8”, to be precise), the regiment would see action at many key battles of the Civil War.23 In the flowery language typical of early 20th century literature, one book described the service and leadership of the 44th in this way: “The men chosen for this command were of the flower of the state and displayed their heroism on many a desperately contested field, where they won laurels for themselves. and for their state.”24

The creation of the 44th New York was not the only reminder Lincoln had of Ellsworth’s passing. The same flag Ellsworth had given his life to remove from the Marshall House was presented to Mary Todd Lincoln. Mrs. Lincoln was, as is fairly well known, an emotional woman, so she hid the flag out of view, perhaps hoping that hiding the flag could diminish her husband’s grief and her own. Tad Lincoln somehow knew where the flag was kept, and he would take it out from time to time and make mischief with it, as he did while his father was reviewing the soldiers.25 Though Lincoln was likely displeased with such interruptions, I would like to think that he was also glad to have the tangible reminder of his young friend and the sacrifice he had made – not for himself, but for his country, and surely also for his friend, President Lincoln.

Notes:

1. (One day…..””offenders within””): Julia Taft Bayne, Tad Lincoln’s Father (Lincoln, NE: Bison Books, 2001), 39-40, quoted in The Lehrman Institute, “Notable Visitors: Elmer Ellsworth (1837-1861),” Mr. Lincoln’s White House, accessed December 6, 2020, http://www.mrlincolnswhitehouse.org/residents-visitors/notable-visitors/notable-visitors-elmer-ellsworth-1837-1861/.

2. (If his is a new name…..officer killed in the Civil War): Emily George, “Elmer E. Ellsworth,” National Museum of the United States Army, accessed December 3, 2020, https://armyhistory.org/elmer-e-ellsworth/.

3. (While Ellsworth was born….money and education): George, “Elmer E. Ellsworth,” https://armyhistory.org/elmer-e-ellsworth/.

4. (Ellsworth then decided….law clerk): Fort Ward Museum, “Col. Elmer Ellsworth and the Marshall House Incident,” Office of Historic Alexandria, accessed December 3, 2020, https://www.alexandriava.gov/uploadedFiles/historic/info/civilwar/EllsworthandtheMarshallHouseIncident.pdf. City of Alexandria, VA.

5. (Through these studies….Chicago National Guard Cadets): Fort Ward, “Col. Elmer Ellsworth…”, https://www.alexandriava.gov/uploadedFiles/historic/info/civilwar/EllsworthandtheMarshallHouseIncident.pdf.

6. Fort Ward, “Col. Elmer Ellsworth…”, https://www.alexandriava.gov/uploadedFiles/historic/info/civilwar/EllsworthandtheMarshallHouseIncident.pdf.

7. Ruth Painter Randall, Colonel Elmer Ellsworth: A Biography of Lincoln’s Friend and First Hero of the Civil War (Boston: Little, Brown, and Co., 1960), 163, quoted in The Lehrman Institute, “The Sons: Elmer Ellsworth (1837-1861),” Mr. Lincoln’s White House, accessed December 6, 2020, http://www.mrlincolnandfriends.org/the-sons/elmer-ellsworth/.

8. The Lehrman Institute, “The Sons,” http://www.mrlincolnandfriends.org/the-sons/elmer-ellsworth/; The Lehrman Institute, “Notable Visitors,” http://www.mrlincolnswhitehouse.org/residents-visitors/notable-visitors/notable-visitors-elmer-ellsworth-1837-1861/.

9. The Lehrman Institute, “Notable Visitors,” http://www.mrlincolnswhitehouse.org/residents-visitors/notable-visitors/notable-visitors-elmer-ellsworth-1837-1861/.

10. Fort Ward, “Col. Elmer Ellsworth…”, https://www.alexandriava.gov/uploadedFiles/historic/info/civilwar/EllsworthandtheMarshallHouseIncident.pdf.

11. Wikipedia, “Elmer E. Ellsworth, “Wikipedai.com, accessed December 7, 2020, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Elmer_E._Ellsworth#:~:text=Studying%20law%20under%20Lincoln%2C%20he,little%20man%20I%20ever%20met%22.

12. Fort Ward, “Col. Elmer Ellsworth…”, https://www.alexandriava.gov/uploadedFiles/historic/info/civilwar/EllsworthandtheMarshallHouseIncident.pdf.

13. George, “Elmer E. Ellsworth,” https://armyhistory.org/elmer-e-ellsworth/.

14. George, “Elmer E. Ellsworth,” https://armyhistory.org/elmer-e-ellsworth/.

15. Fort Ward, “Col. Elmer Ellsworth…”, https://www.alexandriava.gov/uploadedFiles/historic/info/civilwar/EllsworthandtheMarshallHouseIncident.pdf.

16. (Ellsworth, of course,…command his Zouaves again): Fort Ward, “Col. Elmer Ellsworth…”, https://www.alexandriava.gov/uploadedFiles/historic/info/civilwar/EllsworthandtheMarshallHouseIncident.pdf.

17. (One of….””Our Country)”): George, “Elmer E. Ellsworth,” https://armyhistory.org/elmer-e-ellsworth/.

18. Owen Edwards, “The Death of Colonel Ellsworth,” Smithsonian Magazine, April 2011, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/the-death-of-colonel-ellsworth-878695/.

19. George, “Elmer E. Ellsworth,” https://armyhistory.org/elmer-e-ellsworth/; Edwards, “The Death of Colonel Ellsworth,” https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/the-death-of-colonel-ellsworth-878695/.

20. (When Lincoln heard…””great regard””): Charles M. Segal, editor, Conversations with Lincoln (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1961), 122-123, quoted in The Lehrman Institute, “The Sons,” http://www.mrlincolnandfriends.org/the-sons/elmer-ellsworth/.

21. George, “Elmer E. Ellsworth,” https://armyhistory.org/elmer-e-ellsworth/; Fort Ward, “Col. Elmer Ellsworth…”, https://www.alexandriava.gov/uploadedFiles/historic/info/civilwar/EllsworthandtheMarshallHouseIncident.pdf.

22. Fort Ward, “Col. Elmer Ellsworth…”, https://www.alexandriava.gov/uploadedFiles/historic/info/civilwar/EllsworthandtheMarshallHouseIncident.pdf.

23. Steve A Hawks, “44th New York Volunteer Infantry Regiment: Unit Details,” The Civil War in the East, accessed December 4, 2020, https://civilwarintheeast.com/us-regiments-batteries/new-york-infantry/44th-new-york/.

24. The Union Army: A History of Military Affairs in the Loyal States, 1861-65 — Records of the Regiments in the Union Army — Cyclopedia of Battles — Memoirs of Commanders and Soldiers, vol. 2 (Madison, WI: Federal Pub. Co., 1908), quoted in, New York State Division of Military and Naval Affairs: Military History, “44th Infantry Regiment, Civil War, Ellsworth Avengers; People’s Ellsworth Regiment,” The New York State Military Museum and Veterans Research Center, last modified March 2, 2019, https://dmna.ny.gov/historic/reghist/civil/infantry/44thInf/44thInfMain.htm.

25. (The same flag….reviewing the soldiers): The Lehrman Institute, “Notable Visitors,” http://www.mrlincolnswhitehouse.org/residents-visitors/notable-visitors/notable-visitors-elmer-ellsworth-1837-1861/.

Image Citations:

Matthew Brady, “Photograph showing portrait of Tad Lincoln, standing, wearing a military-style uniform,” c. 1864, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Tad Lincoln in uniform – Tad Lincoln – Wikipedia.

“Col. Elmer Ellsworth,” The Photographic History of The Civil War in Ten Volumes: Volume One, The Opening Battles (New York: The Review of Reviews, 1911), 350, in Wikipedia, “Elmer E. Ellsworth,” Wikipedia.com, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Elmer_E._Ellsworth#/media/File:ElmerEllsworthphoto01.jpg.

Aleksander Raczyński, “French zouaves during the Crimean war; painting by Aleksander Raczyński,” 1858, accessed December 6, 2020, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zouave#/media/File:RaczynskiAleksander.ZuawiWWalce.1858.jpg

“Marshall House, Alexandria, Virginia – place where Elmer Ellsworth was shot to death,” in The Photographic History of The Civil War in Ten Volumes: Volume One, The Opening Battles (New York: Review of Reviews Co., 1911), 351, in Wikipedia, “Marshall House (Alexandria, Virginia),” Wikipedia.com, accessed December 6, 2020, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marshall_House_(Alexandria,_Virginia)#/media/File:MarshallHouse1861.jpg

A. L. Hudson, “Ellsworth’s Avengers” (Boston: Horace Partridge, 1860s), Repositoryhttps://repository.duke.edu/dc/broadsides/bdsma10768.

Interesting post, Anna! This was all new information to me. Keep the posts coming (as you have time and inclination!).

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much, Deborah!

LikeLiked by 1 person