Writing in 1862, the Union Army officer John McHarg mournfully said to his little brother, “I have just reminded Father of the change since last New Year’s Day, & the many calls that will be missed on account of this horrid war.”1 The “horrid war” John referred to was, of course, the Civil War, which separated numerous families during the holiday seasons of 1861-1865. Though we might not be at war right now, many of us will also spend our holidays in a more solitary fashion than usual because of the ongoing pandemic. While this will make for a bittersweet Christmas season, I find comfort and some amusement in reflecting on how Civil War Union soldiers navigated times of separation with courage, fortitude, and even a degree of frivolity. So, exactly how did these soldiers create some holiday fun for themselves in the middle of a Civil War, far from their loved ones?

The 44th New York Infantry Regiment, whose creation I described in my previous post, provides a fun example of how Civil War soldiers celebrated that first Christmas of 1861. Though John McHarg did not serve with the 44th New York (John was at a higher level in the army’s organizational structure), he did offer a short description of the 44th’s Christmas day festivities. Coming from a fairly well-to-do family in Albany, NY, John was likely familiar with comfortable, if not lavish, Christmas gatherings. But, the 44th’s celebrations were surely quite different from anything he had experienced in previous years! On January 1, 1862, John wrote:

“I have this afternoon been over to see a comic parade of the 44th but I do not think that it was as good as on Christmas, but it may be that it was stale to me having once seen it. On the spot was “Our Special Artist” of the Harpers Weekly, so in the course of a week or two you will be able to see the photograph of the 44th “en costume”.”2

As John stated, he enjoyed Christmas (and also the New Year) by watching a “comic parade” the 44th New York Regiment put together for the enjoyment of other officers and soldiers. Moreover, apparently this parade was so memorable that an artist from one of the key periodicals of the time even illustrated the event. This led me to wondering what the details were of the 44th’s yuletide “comic parade”? And, how did other Civil War Union soldiers celebrate Christmas in the winter of 1861?

The 44th New York’s Christmas Celebrations

The 44th New York arrived in the Washington, D.C., area in October of 1861, and there they would celebrate Christmas with John McHarg and many other officers and soldiers.3 Christmas day itself was spent in great frivolity, according to A History of the Forty-Fourth Regiment. The day’s activities, including a game of ball in the morning and the “comic parade” in the afternoon, occurred primarily for the benefit of the enlisted men, though – as John hinted – the officers enjoyed the festivities as well.4

The 44th’s comic parade, Frank Leslie’s Illustrated – full citation below

As you can see in the above image, the parade featured amusing costumes and mock weaponry. Described by the author of A History of the Forty-Fourth Regiment, Eugene Nash, the parade began with the officers relinquishing their commands to the enlisted men, who then organized the farce. The rank of Colonel was taken on by Bob Hitchcock, a man deemed memorable by Nash because of his stature, weighing in at around 300 pounds. But, the author also noted Hitchcock because of his great enthusiasm for his “duties,” which he demonstrated by riding backwards on his horse (who was wearing “trousers on his fore legs, and a pair of drawers on his hind legs”5) so as to never lose sight of the men under his command. The other men following behind their temporary “colonel” also wore comical outfits, such as the hoopskirt prominently featured in Frank Leslie’s illustration.6 As a whole, Nash described the parade as more comical than even Falstaff, a comedic Shakespearean character.7 Then, a humorous court martial was held, though the punishments were only as severe as helping the cooks with their preparations. The author concluded that, “it was all very amusing and whatever was said or done was treated with the utmost good humor.”8

While the parade clearly demonstrated that the men found ways of celebrating Christmas with joy, the author did hint at a degree of melancholy that winter. When referencing Frank Leslie’s (referred to by John as ““Our Special Artist” of Harpers Weekly”) illustration of the event, Nash believed that Leslie failed to capture the humor and joy of the parade, which remained “in the memory like a bright spot in that winter’s experience of army life.”9 This statement indicates that, much like we might need to find a “bright spot” in winter during this pandemic, so also the Union Army men clung to happy memories during the challenging periods of that first winter of the war.

Union Army Christmas Celebrations

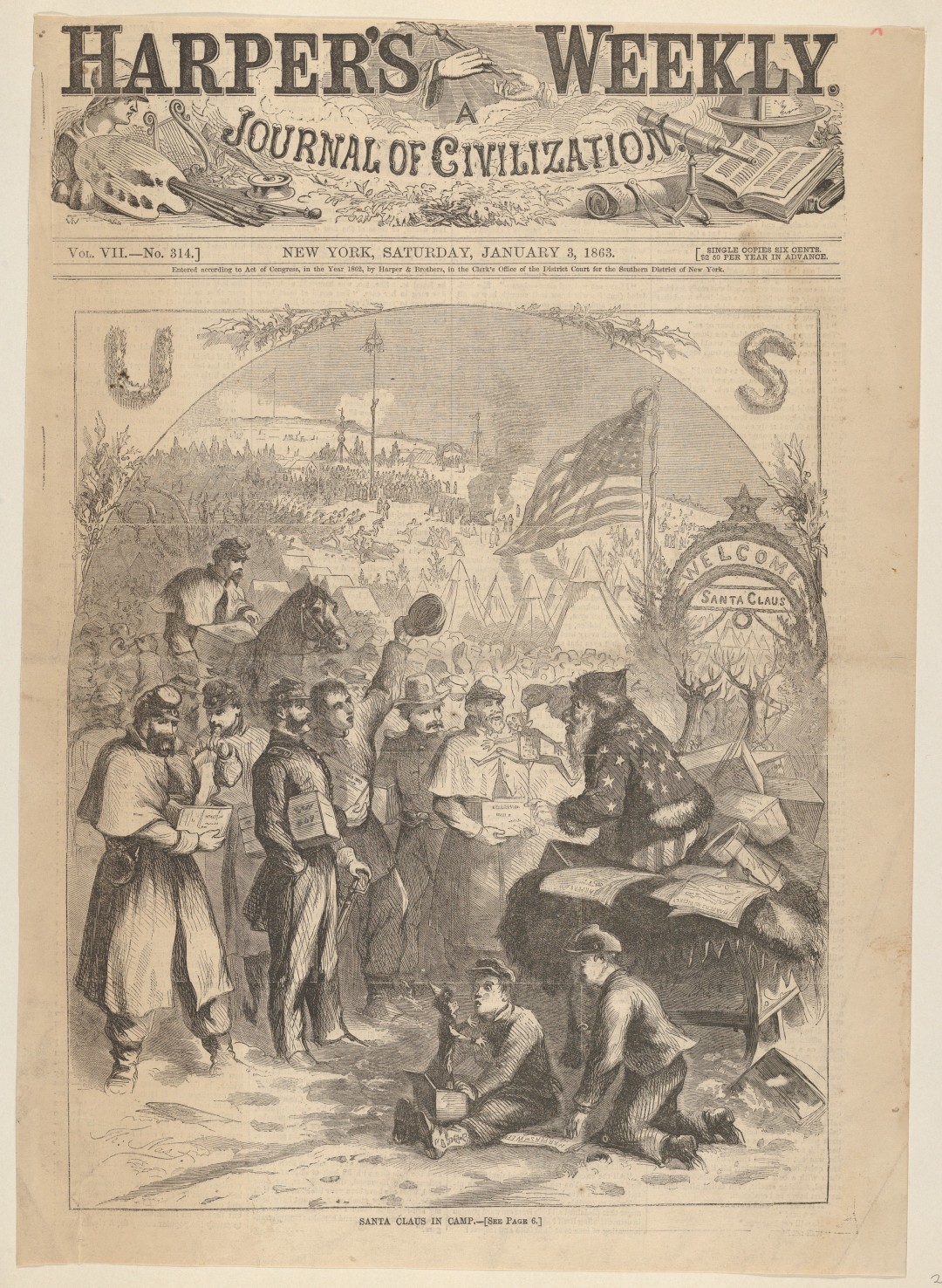

The 44th’s comic parade was only one of the various festivities Union soldiers embraced, many of which reflected the new (at the time) Christmas traditions we now think of as synonymous with the season. In the mid-1800s, the Christmas season transformed from an austere celebration, as encouraged by the Puritans, to a time of merriment, feasting, decorations, parties, and gift giving.10 These traditions and activities reflected the older, European ways of celebrating the season, which Charles Dickens had expanded with his publication of A Christmas Carol.11 Some of these traditions included the Christmas tree (compliments of the Germans); the yule log, caroling, Christmas cards, and mistletoe (for which we are indebted to the English); and Santa Claus (originating with the Dutch).12 The German immigrant cartoonist, Thomas Nast, expanded the idea of Santa Claus in 1861, when he provided an illustration to accompany Harper’s Weekly’s publication of Twas the Night Before Christmas.13 Nast’s Santa Claus was fittingly portrayed as distributing gifts to the Union soldiers.14

While Union soldiers’ accounts of that first wartime Christmas often fail to mention a visit from Santa Claus, they do demonstrate the ways in which soldiers embraced Christmas festivities in their army camps. Some soldiers managed to decorate their tents with a Christmas tree, though the ornaments were limited to “”hard tack and pork, in lieu of cakes and oranges, etc.””15 Festive activities included “foot races, wrestling, and snowball fights,” with the winners often receiving money as a prize.16 Other soldiers, like those of the Irish Brigade, celebrated Christmas Eve with songs and dancing, in which activity the brigade’s black servants also participated, according to David Power Conyngham.17 The evening’s frivolities concluded with the celebration of midnight Mass, when the men had the opportunity of hearing the true Christmas story read from the Gospels by the chaplains.18 The next morning, the Brigade celebrated Mass once again and then enjoyed companionship, conversation, and pipes for the rest of that Christmas day.19 Some soldiers reported receiving Christmas packages from their families, filled with supplies and foods.20 Sumptuous meals brightened Christmas for some regiments, but many men undoubtedly arose the next day with raging headaches after imbibing a great deal of alcohol to wash down their holiday feasts.21

No matter how much feasting or how many festivities the men enjoyed on that Christmas day, the pain of separation from their loved ones still cast a shadow over their celebrations. While John McHarg’s letter to his brother displays a fairly matter of fact tone, other soldiers’ letters reflected homesickness. For some, their Christmas letters reported boredom and bittersweet reminiscences of past holidays spent with their families.22 When reflecting on Christmas Eve of 1861, Conyngham wrote “No wonder if, amidst such scenes, the soldier’s thought fled back to his home, to his loved wife, to the kisses of his darling child, to the fond Christmas greeting of his parents, brothers, sisters, friends, until his eyes were dimmed with the dews of the heart.”23 Others were especially cognizant of the turmoil the divided nation faced.24 Perhaps it is a blessing that those soldiers did not then know the many years the war would continue, or the tragic number of lives lost in the conflict.

Though we are thankfully not currently engaged in a civil war, the example of these Union soldiers can inspire us to find joy in the Christmas season. The soldiers did grapple with their sorrow over the separations caused by war, and so we too might find ourselves reflecting on past, pandemic-free holiday seasons. As David Anderson wrote, as quoted by Erin Blakemore, “”The Christmas season [reminded] mid-19th century Americans of the importance of home and its associations, of invented traditions.””25 Likewise, we too can take comfort in Christmas traditions (even if they don’t include a “comic parade”) – setting up our Christmas trees, sending cards and packages to family and friends, listening to Christmas music while baking cookies. All of these things can provide a small sense of normalcy in this disturbed year, and a hope that brighter days will come. I trust that, when we are once again able to gather freely with family and friends, we will rejoice all the more for the blessings of togetherness.

Notes:

1. John William McHarg to Henry McHarg, January 1, 1862, McHarg Family Papers, 71701. Georgetown University Manuscripts, https://findingaids.library.georgetown.edu/repositories/15/archival_objects/1198629.

2. John William McHarg to Henry McHarg, January 1, 1862, https://findingaids.library.georgetown.edu/repositories/15/archival_objects/1198629.

3. Steve A Hawks, “44th New York Volunteer Infantry Regiment: Unit Details,” The Civil War in the East, accessed December 4, 2020, https://civilwarintheeast.com/us-regiments-batteries/new-york-infantry/44th-new-york/.

4. Eugene Arus Nash, A History of the Forty-Fourth Regiment, New York volunteer Infantry, in the Civil War, 1861-1865 (Chicago: R. R. Donnelley & Sons Company, 1911), 56, https://archive.org/details/historyoffortyfo00nash/page/56/mode/2up\.

5. Nash, A History of the Forty-Fourth Regiment, 56, https://archive.org/details/historyoffortyfo00nash/page/56/mode/2up\.

6. Nash, A History of the Forty-Fourth Regiment, 56, https://archive.org/details/historyoffortyfo00nash/page/56/mode/2up\; “Christmas, New Years, The 44th Regt, N.Y.S. Vol.,” Frank Leslie’s Illustrated, (New York: Frank Leslie), January 18, 1862, 136-137, https://archive.org/details/franklesliesilluv1314lesl/page/136/mode/2up.

7. Nash, A History of the Forty-Fourth Regiment, 56, https://archive.org/details/historyoffortyfo00nash/page/56/mode/2up\; The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica, “Sir John Falstaff,” Encyclopaedia Britannica, accessed December 4, 2020, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Sir-John-Falstaff.

8. Nash, A History of the Forty-Fourth Regiment, 57, https://archive.org/details/historyoffortyfo00nash/page/n93/mode/2up.

9. Nash,A History of the Forty-Fourth Regiment, 57, https://archive.org/details/historyoffortyfo00nash/page/n93/mode/2up.

10. The Smithsonian Associates, “Christmas North and South,” The Smithsonian Associates Civil War E-mail Newsletter 4, No. 7, accessed December 5, 2020, http://archive.is/HShx.

11. The Smithsonian Associates, “Christmas North and South,” http://archive.is/HShx; The American Battlefield Trust, “Christmas During the Civil War,” The American Battlefield Trust, https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/christmas-during-civil-war.

12. Kevin Rawlings, We Were Marching on Christmas Day: A History and Chronicle of Christmas During the Civil War (Baltimore: Toomey Press, 1996), 2 12, 6, 9.

13. The Smithsonian Associates, “Christmas North and South,” http://archive.is/HShx.

14. The Smithsonian Associates, “Christmas North and South,” http://archive.is/HShx.

15. The American Battlefield Trust, “Christmas During the Civil War,” https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/christmas-during-civil-war.

16. Rawlings, We Were Marching on Christmas Day, 41.

17. David Power Conyngham, The Irish Brigade and its Campaigns: With Some Account of the Corcoran Legion, and Sketches of the Principal Officers (Glasgow: R & T Washbourne, 1866), 39-40, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uiuo.ark:/13960/t16m88d8q&view=1up&seq=46&q1=Christmas.

18. Conyngham, The Irish Brigade and its Campaigns, 41, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uiuo.ark:/13960/t16m88d8q&view=1up&seq=47&q1=Christmas.

19. Conyngham, The Irish Brigade and its Campaigns, 42. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uiuo.ark:/13960/t16m88d8q&view=1up&seq=48&q1=Christmas.

20. Rawlings, We Were Marching on Christmas Day, 47-48.

21. Rawlings, We Were Marching on Christmas Day, 46, 45.

22. Rawlings, We Were Marching on Christmas Day, 40.

23. Conyngham, The Irish Brigade and its Campaigns, 39, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uiuo.ark:/13960/t16m88d8q&view=1up&seq=48&q1=Christmas.

24. The American Battlefield Trust, “Christmas During the Civil War,” https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/christmas-during-civil-war.

25. Erin Blakemore, “How the Civil War Changed Christmas in the United States,” History.com, January 15, 2019, https://www.history.com/news/civil-war-christmas.

Image Citations:

Thomas Nast, “Santa Clause in Camp,” Harper’s Weekly, January 3, 1863, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Santa_Claus_in_Camp_(from_Harper%27s_Weekly)_MET_DP831805.jpg.

“Christmas, New Years, The 44th Regt, N.Y.S. Vol.,” Frank Leslie’s Illustrated, (New York: Frank Leslie), January 18, 1862, 136-137, https://archive.org/details/franklesliesilluv1314lesl/page/136/mode/2up.

Thomas Nast, “A Husband and Wife Separated by War,” Harper’s Weekly, January, 1863, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Christmas_in_the_American_Civil_War#/media/File:Thomas_Nast_illustration_of_a_couple_separated_by_war,_January_1863.jpg.

I must admit, I don’t spend much time pondering similarities between Civil War days and now. Thanks for prompting me to do so, in an interesting and informative way, as we head into a unique Christmas week!

LikeLike