While traveling on the Newbern, Martha experienced one of the least enjoyable aspects of a long journey – bad food. As you might recall from last week’s post, Martha’s day typically began with a light meal of black coffee and hardtack before a proper breakfast was served (25). To taste what Martha nibbled on with her morning coffee, I decided to try making hardtack in my own kitchen.

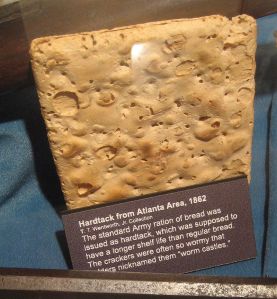

As is commonly known, hardtack was a dry, cracker type of bread typically used for long journeys on sea or land, and also included as part of a Civil War soldier’s rations. If you’d like a more thorough explanation of the history of hardtack, I recommend videos from two of my favorite historical cooking YouTube channels: Townsends and Tasting History. These two videos helped provide me with excellent contextual information on this staple item, and they both do a great job of explaining how to create hardtack in your own kitchen. In brief, though, hardtack was a relatively tasteless but essential item which was valued for its longevity. Unlike traditional, tasty soft breads, hardtack was often baked twice over and consequently stayed fresh for much longer (Townsends). Before you get excited thinking that soldiers and travelers were basically eating a savory biscotti, which is also baked twice, hardtack was baked to the nearly inedible point. In extreme cases, soldiers would report breaking their teeth on their daily portions. At the very least, hardtack required a good long soak in soup, coffee, water, or anything else before it was actually edible. As if it could get any worse, hardtack was also often kept around for far too long, even past its admirably long shelf life. Soldiers would report finding bugs literally worming their way through the crackers, but necessity compelled them to eat the hardtack anyway. According to the excellent video by Townsends, sailors sometimes opened up barrels of hardtack only to find the barrels filled with roaches, which had already devoured the food.

After reading the above, you might be wondering why you would ever want to make this. Keep reading, and I’ll have some suggestions for you on how to make this slightly more palatable!

To create my hardtack, I combined Tasting History’s and Townsends’s recipes into one. Per Max Miller’s instructions on Tasting History, I combined four cups of flour with some water. While stoneground flour is recommended as more historically accurate, the stoneground flour I happened to have on hand is on the pricey side, so I sacrificed only two cups to this tasteless (I mean, historical) endeavor and used regular unbleached flour for the other two cups. In keeping with Townsends‘s video and this article by The American Table, I also added some salt with the rationale that it would help with flavor and act as an additional preservative. Since my flour was absorbing the water very quickly, I probably added a grand total of about one and a half cups of water.

Next, I started kneading the dough. As Max Miller instructed, I kneaded for about fifteen minutes in all. I added a bit of flour to the dough throughout the kneading process to prevent sticking. Fifteen minutes and one very sore wrist later, I cut the dough into eight equal portions, rolled each into a ball, and shaped each ball into a little flat biscuit. Then, I poked holes into the biscuits with a very advanced baking tool: the Chinese food take-out chopstick.

At this point, it was time to begin the baking process – and I truly mean process. Setting my oven at 300 degrees, I left those poor biscuits in there for not one, not two, but for three hours. Then, after they’d cooled over night, I placed them back in the oven at 200 degrees for an additional two hours. However, I only baked four of them twice, and saved out the other four for a comparison.

After cooling, I attempted to take a bite – and I could not. I dipped the once baked piece into water, but it absorbed the water immediately. I tried to sample the twice baked hardtack but could not break any of it off. Without any exaggeration, even our meat hammer succeeded in only chipping off a few bits of the edge after a couple really hard whacks. I took these little edge bits and a piece of the once baked hardtack and put both in separate glasses with a little water. After about half an hour to an hour of soaking, the pieces were barely edible. I’ll be honest, the taste was not horrible! Thanks to the salt and the nuttiness of the stoneground wheat flour, the biscuits tasted more or less like a hearty, thick saltine cracker. Of course, it helps if you can eat these crackers without stressing over your dental health or without soaking in liquid for an hour. I’m not sure how, but my husband and a neighbor both managed to actually eat some of the hardtack without going to such extreme soaking methods – and their teeth survived! But for me, I didn’t fancy a trip to the dentist, so I thought of some ideas for how to make this biscuit without worrying about a cracked tooth.

If you would like to make a more palatable version of this in your kitchen, I’d suggest the following changes. First of all, I would definitely recommend using at least half a tablespoon of Kosher salt (less if using table salt), as directed in the recipe from The American Table. As stated earlier, the stoneground wheat flour improves the flavor, so splurge a little and purchase some (you can use the leftover stoneground flour to make Irish brown bread, which is the most wholesome, comforting bread, in my opinion). I would also add a bit more water. Of course, you’ll need to be able to knead the dough, but more water would help prevent the hardtack from getting so very dry in the oven. Finally, I would bake the hardtack for only thirty to forty-five minutes, at the very most. With these few changes, I think hardtack could be transformed into a pleasant accompaniment to soup or salad.

I wish Martha had described more thoroughly how she ate her hardtack. Her description of it is offered in such minimal detail that I can only imagine she soaked it for a good long time in her black coffee – but alas, the reader is left to speculate on her methods of benefitting from this morning snack. Stay tuned for next week’s post, in which Martha’s experiences on her journey to Arizona will go from bad to worse.

Bibliography

Summerhayes, Martha. “Chapter 4: Down the Pacific Coast.” In Vanished Arizona: Recollections of the Army Life by a New England Woman, 23-28. Scotts Valley, CA: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2017. First published 1911.

Miller, Max. “Tasting History: How to Eat Like a Pirate: Hardtack and Grog.” YouTube Video, 18:30. February 2, 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oPTdSMOQRnY&t=24s.

Townsends. “Ships Biscuit – Hard Tack: 18th Century Breads, Part 1. S2E12.” YouTube Video, 9:01. May 14, 2012. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FyjcJUGuFVg.

Colleary, Eric. “Civil War Recipe: Hardtack (1861).” The American Table. June 26, 2013. http://www.americantable.org/2013/06/civil-war-recipe-hardtack-1861/.